Read.

When your world seems to be crumbling, read.

When faced with a world that makes no sense, read.

When you think you are overwhelmed, read.

When you think you know the answers, read.

When you don’t know what people are thinking, read.

When you believe you know what people are thinking, read.

Read Ta-Nehisi Coates. Read James Baldwin. Read Toni Morrison (I’ve yet to, but in the queue). Read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Zadie Smith, Marquez, Eco, Amitav Ghosh, Orhan Pamuk. Read Laxman Gaikwad (Uchalya उचल्या), Daya Pawar (Baluta बलुतं), Anand Yadav (Zombi झोंबी) or such writers from your native languages. Read feminist literature. Read anti-colonialism literature, like Eduardo Galeano (Open Veins of Latin America).

The tales of disenfranchised are terrible tales even to read sometimes (not terrible artistically, terrible because they make it hard to breathe). Yet those tales — non-fiction, or fiction-capturing-reality — are our nearest path to vicariously live a tiny part of those lives, and understand a tiny part of being someone we’re not. Given how the world is divided into haves and have nots, if you are an educated person, you’re (most likely) a privileged person. Maybe you share directly a part of some of those other experiences, but it’s a remote possibility that you share many of them. The only way to recognize privilege — because it’s like what David Foster Wallace identified in his famous commencement speech, “this is water”, the everyday reality around you is hardest to see, especially when you are in the driving seat — is to see reality through other people’s eyes. The people not like us. People on the wrong side of history (it’s easy for us to see the ravages of colonialism on our psyche, but not what majoritarianism does to minority experience when you’re not a minority).

As Wallace said in that commencement speech: “if you really learned how to think, how to pay attention (and I will add: how to see), then you know you have other options”. Other than your default settings — the ones you inherited by being part of a sub-culture, typically a privileged sub-culture (typically for people who are likely to even have time to read this).

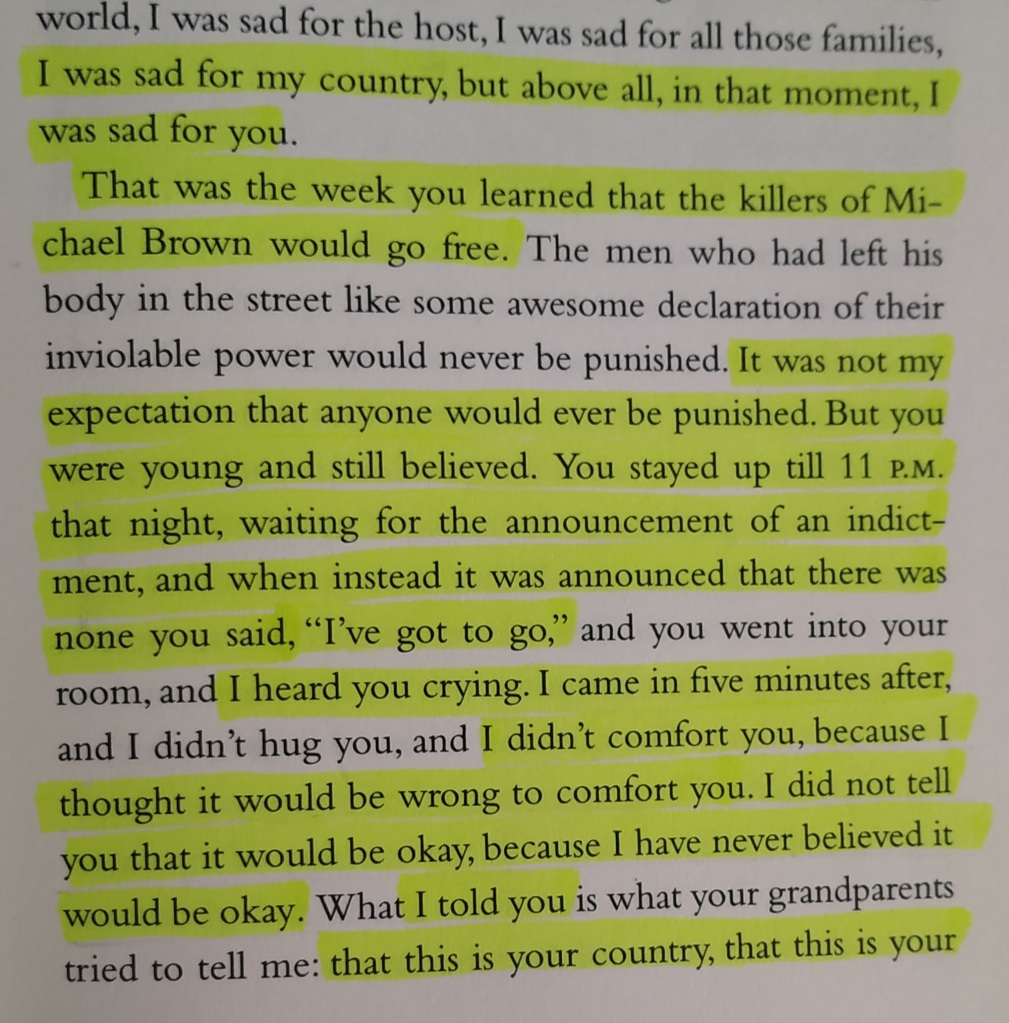

Yes Zombi, Baluta, Uchalya changed the way I thought about merit — that elusive word people like me hid behind to protect our privilege of being born in families that treasured education and had the means to pass it on to their children. I cried, copiously, reading Ta-Nehisi Coates, years later, learning again about experiences that thankfully I never had to have first-hand. I recall furiously marking on the book — something I used to think of a sacrilege. But when society is leaving its marks on the bodies of humans, and indeed bodies of humans as a mark on our civilization, what’s a book with underlines and highlights?

Yes, I’m way away from America, with zero skin in the game. But every experience of disenfranchised has something to teach us — to question our societies, our governments, our institutions. For every #BLM, there are Kashmir lives, there are Dalit lives, there are Muslim lives (and Hindu/Jain/Buddhist lives in Pakistan and other Muslim countries), there are trans lives, going through a different, yet similar experiences.

By reasserting — truthfully, not as a token/fad — in this moment #BlackLivesMatter, we reclaim the right to assert that the disenfranchised lives matter in our backyards. It’s not exclusivist, but inclusivist. It’s how we treat our weakest decides what we are. Our humanity sets us apart from the so-called “cruel” animal world, but what is that humanity if it’s not introspective, conscientious, empathetic, and just? If it’s vindictive, vain, self-serving, cruel, and destructive — it’s still unique in this world, for animals can’t be any of it, but is that what we aspire to be? It’s not our uniqueness, but how we are unique that matters, for otherwise, psychopaths and saints are equally unique.

James Baldwin famously said: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive”. That connection is uniquely human. In a good way, that is. In an excellent way, actually. So yes, I’ll repeat: read, read, read!